I come from a country that no longer exists. In autumn 2011, two decades after its collapse in the early 1990s, I set out on a journey to find Yugoslavia. The fact that the country I was born and raised in no longer existed on the map didn’t matter.

Marshal Tito’s Yugoslavia gave holidaying Brits their first taste of foreign travel in the then-president’s “workers’ paradise”, helping to invent the present-day package holiday.

Marshal Tito’s Yugoslavia was the holiday destination that discovered us. From the 1950s onwards, millions of Brits had their first taste of going abroad in the then president’s state- planned ‘workers’ paradise’.

He paved the way for modern-day tourism, which now contributes more than 63 million overnight stays to Croatia alone. Bosnia-Herzegovina is now known as one of the friendliest places to visit and tiny Montenegro is regularly praised for its beauty.

Tito’s centrally-planned and brazenly political grab for the Western tourist market set the agenda for how we holiday today. Karin Taylor, co-editor of Yugoslavia’s Sunny Side, says: “Yugoslavia was the first country to realise the importance of foreign tourism for the creation of much needed revenue and ultimately for generating hard currency.

“This had to do with the 1948 break from Moscow when the country desperately needed to aid its struggling economy, as well as to establish itself independently on the international stage.”

Lured by low prices (Tito devalued the dinar to make Yugoslavia cheap for Westerners) stunning coastlines, and the intriguing invitation to ‘Come and see the truth for yourself,’ Brits flew in from all corners of the UK to savour the sunny socialist paradise.

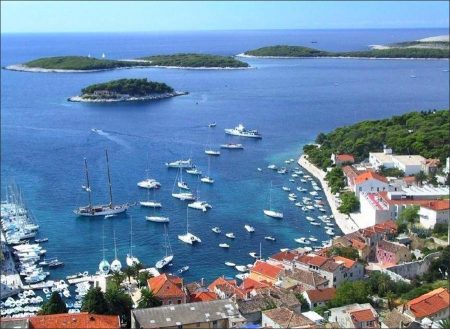

Holidaymakers were deposited along the Adriatic coast at Pula, Split and Dubrovnik (part of what is now Croatia) and whisked off by coach to purpose-built, landscaped resorts.

From holidaymakers to adventurers

Tito encouraged tourism and Brits became adventurous, often on ‘two-centre’ Yugoslav holidays Secure in a cocoon of holiday reps and government-sponsored tourist information guides, under Tito’s vision Brits took their first steps to being more adventurous travellers.

Iain Fenton, former national sales manager for package operator Yugotours, says: “Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Brits travelled to Spain and the Canaries, maybe a few to Greece and Yugoslavia, and that was about it.

“We found they came to Yugoslavia once, probably to Istria, and then became more adventurous on their subsequent trips, going south to Dubrovnik and Montenegro.

“This encouraged two-centre holidays, which were considered very adventurous at the time.”

Meeting local people was also an essential part of the Yugotours package promise, just as experiencing the ‘real’ Cambodia, Equador or Sri Lanka is an aspiration for travellers today.

In theory, package tourists holidayed side by side with Yugoslav workers, enjoying state-sponsored leisure at newly built ‘odmaraliste’ recreation centres. Yet in reality the influx of comparatively affluent tourists drove up prices and made coastal resorts expensive for locals.

Some socialist commentators worried about the imported cultural values of consumerism and sex. International tourism was seen as a major site of struggle between two moral systems.

Or as rephrased by my cousin Beverley: “The hotel discos were full of Romeo waiters trying to get fresh.” She was on her first ever continental holiday in the late 1970s, celebrating finishing secretarial studies at Wisbech Tech.

As time wore on, Yugoslavia’s centrally-generated hunger for Western tourists “inverted social principles,” according to art historian Maroje Mrduljas. “Caught in a frenzy of growth predictions, planners made precise calculations of hotel accommodation and other tourist facilities, but tended to ignore the needs of the local population.”

Under socialist economic principles of infinite growth, planners even worked out the amount of available beach space per tourist: one metre of beach per 1.66 tourists, with a factor of 1.4 in the case of simultaneous use.

Off the beaten track

Yugoslavian package tours often took Brits beyond the beach and on inland excursions. Yet Brits did not have to wander too far from their Modernist concrete resorts to encounter activities that have now become travel trends. Wild camping was a budget way for young Yugoslavs to enjoy their paid holiday fortnight.

Naturism was also officially promoted by the regional Croatian Tourism Development Association and in 1982, the first Yugoslavia naturist guide brochure was printed.

Yugotours excursions were another driver in taking holidaying Brits beyond the beach. Recalling his first trip abroad as a 20-year-old, in 1977, charity volunteer Paul says a fortnight in Opatija (part of what is now Croatia) was a springboard for coach trips to the Postojna Caves, Plitvice Lake National Park, and the island of Krk.

And while some excursions were expected to yield a profit for Yugotours, others could run for political reasons, or because a region needed to be ‘discovered’ by hard currency-holding tourists.

The “recreation for the regeneration of labour” that Tito believed would make better workers and socialists of his own subjects rubbed off onto the country’s visitors.

“They were not ‘fly and flop’ holidays,” says Fenton. “It was usual to take excursions along the Istrian Peninsula, or boat tours, or to go inland. Mostar, for the bridges, was always popular.”

Brits to try new food and drink

For my cousin Beverley, having white wine with her evening meal was a revelation. I remember her postcard from Umag (Croatia) at the end of the 1970s, marvelling at fish without batter, squid, oysters, and ravioli with no sauce. The price of capitalist Coca-Cola was Bev’s only gripe.

Holidaying in 1970s Yugoslavia, ordinary Brits eased off packing a bottle of brown sauce in their luggage as a prophylactic against the strong flavours of foreign food.

Instead, for the first time, they saw truffles, asparagus and wild mushrooms on sale for working people in markets and tasted Turkish coffee and croissants in cafes, under Rovinj’s Venetian bell towers.

By the end of the 1980s, before Yugoslavia’s break up, the country was the UK’s second most popular overseas holiday destination.

Even families who did not see themselves as package holiday types booked Yugotours holidays, because they found the history, landscape and the whole variety fascinating according to Fenton. And the cost was attractive: “Your pound went a long way,” he says.

Yugotours’ legacy in your summer holidays

Now we still expect holidays to be a bargain, and obsess about a destination’s cheapness. Equally, we feel deprived if we do not clock up a certain amount of culture and sightseeing while away: it’s our ‘experiential capital’ to share with friends.

And while we pride ourselves on being independent travellers with the role of the travel agent and brochure usurped by the internet and Lonely Planet guides, we still allow specialists to smooth out arrangements when touring distant countries like China and India.

Yugoslavian tourism and the ideology behind it helped the masses take their first baby steps into the holidaying unknown. And the fact that overseas travel is now part of everyday conversation for millions is possibly Tito’s greatest legacy of all.

Views: 943