I had reached Capri by a circuitous route, driving down the coast of the former Yugoslavia before taking a car ferry across the Adriatic to Italy. My intention was to see what the war between Serbs and Croats had done to the famous Dalmatian coast and, in particular, to a favorite island, Hvar (pronounced ‘var).

The start of this drive had been anticlimactic. Instead of the war-torn country I was braced for, everything along the coastal highway was operating normally, the ferries were running on time, and the hotels were brightly lit and in good repair. The only difference from my visit in 1989 was the almost complete absence of tourists, but that I was very happy to live with. (The Dalmatian coast is Germany’s and Austria’s easiest access to the Mediterranean, and in a normal summer it is hit by a blitzkrieg of family vacationers.) It was only later, while taking a shortcut inland from Zadar, that I found myself driving through miles of devastation, with village after village systematically destroyed.

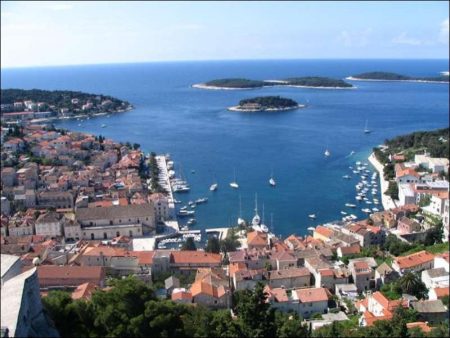

The islands of the Dalmatian coast are the most architecturally beautiful in the world. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the warring between Venice and Ragusa (Dubrovnik) left a legacy of handsome fortified cities built of honey-colored stone, of which Hvar’s is the finest. It is fashioned around an enormous piazza, a Baroque cathedral at one end, a small-boat harbor at the other, and is flanked by Gothic Venetian palaces. Occupying one corner is a building known as the Arsenal: It is topped by a theater that was built in 1612, when Shakespeare was still alive, and is claimed to be the oldest public theater in Europe.

Along with other islands of the Dalmatian coast, Hvar was untouched by the war, except for being used to house refugees. At one time, there were twelve thousand of them, many from the most brutal areas of “ethnic cleansing”: Mostar and Vukovar. Being mostly Muslim peasants, few adapted to island life, and almost all left at the earliest opportunity. Apart from harvesting the lavender crop, grown on the east side of the island, there was no agricultural work for them todo on Hvar.

In trying to reestablish its tourist trade, Hvar, along with the rest of the former Yugoslavia, finds itself in an unfamiliar position. While other Eastern European nations have spent the last seven years slowly adapting to the needs of sophisticated Western travelers, Croatia and Serbia have, because of the war, been standing still. There was a time when, in tourism terms, Yugoslavia was the most Westernized of the Communist nations-but no more.

It was a shock to revisit Hvar and find so many of the old Communist-era habits still in place: waiters staring at their shoes as you try to get their attention; officious managers directing you unapologetically to the worst table or the worst room in the house; charmless staff who do not even offer a good morning, let alone help with your bags; and doormen who look amazed when you ask for an umbrella in the pouring rain. I noted all of those things in Hvar’s four-star Palace Hotel. Nothing was any worse than it had been on my previous visit, but seven years have passed and expectations have changed. The most frustrating thing is that the Palace, beautifully sited between harbor and piazza, behind an exq uisi te sixteenthcentury loggia, has the potential to be one of the prettiest small hotels in Europe.

Now that the war is over, will a change of attitudes come? I was alarmed to learn that Hvar’s ten hotels, including the Palace, have been merged into a single company that is more than fifty percent bank-owned and thirty-eight percent worker-controlled-s-not, on the face of it, a formula for sophisticated new thinking. The most hopeful signs are in the little restaurants of the old town, which are energetically run by eager yo ung entrepreneurs. One wai ter searched for me all over town to return a guidebook I had accidentally left behind.

Hvar is still one of my favorite islands-with its Venetian piazza and lavenderscented hills, it is too beautiful not to be-but I am looking forward to the day when a new generation takes over from those old Palace timeservers.

Vernacular architecture, the high architecture of Hvar, is what most islands are about. And because of the cultural isolation, the constraints on available materials, and the ingenious solutions required by the need to relate to the sea, island architecture is an especially rich vein of folk art.

Greece, of course, has the most instantly recognizable vernacular architecture: not only the white-cube style of the Cyclades, so beloved oftourist posters, but the jaunty red pantiles of northern Greece and the neoclassical pediments of the Dodecanese.

Despite their touristy ambience, Santorini and Mykonos have the two supreme white-cube towns, and nobody can deny that, of the two, Santorini’s has the more dramatic situation, clinging a thousand feet up to the precipitous lip of a sunken volcano. It makes a perfect cruise-ship stop, and the view is a must for first-time visitors; but for me, that is where the attraction ends. Santorini’s town, so pristine and . peaceful from a distance, is unexpectedly tacky at close quarters.

The treadmill of backpackers and sightseers arriving briefly to register the view before squeezing onto the narrow black sand beach gives it a feeling more of a transit camp than of a lazy Greek island. Mykonos, too, suffers from an excess of visitors, but it manages to receive them with a sense of style and chic that has been lost on most other major tourist islands. On my trips to Greece, I always enjoy spending a few civilized days on Mykonos, but “Been there, done that” is my normal response to Santorini.

Views: 291