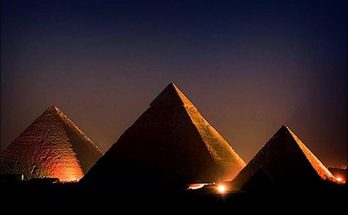

It is a curious chance that the most ancient monuments of human civilization should stand upon a land which is one of the youngest geological formations of our earth.

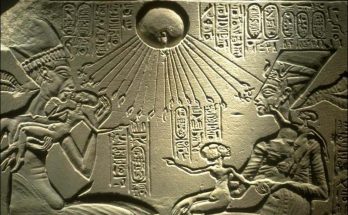

The scene of that artistic activity made known to us by the oldest architectural remains of Africa and of the world was not Upper Egypt, where steep primeval cliffs narrow the valley of the Nile, but the alluvion of the river’s delta. It would be difficult to decide whether the impulse of monumental creativeness were here first felt, or whether the mere fact of the preservation of these Egyptian works, secured by the indestructibility of their construction as well as by the unchangeableness of Egyptian art, be sufficient to explain this priority to other nations of antiquity — notably to Mesopotamia.

Although no ruins have been found in Chaldaea of earlier date than the twenty-third century B.C., it is not at all impossible that remains of greater antiquity may yet come to light in a country which is by no means thoroughly explored. Nor should we deem the old est structures now preserved to be necessarily those first erected. The perishable materials of the buildings which stood in the plains of the Euphrates and Tigris, generally sun-dried bricks with asphalt cement, were not calculated to insure long duration, or to prevent their overthrow and obliteration by the continual changes in the course of these rivers, through the silting and swamping of their valleys. Yet, though tradition would incline us to assume that Chaldaean civilization and art were the more ancient, the oldest monuments known exist upon the banks of the Nile.

Views: 324