Bloomington (830 alt., 74,975 pop.), seat of McLean County, and its sister city, Normal (790 alt., 45,386 pop.), lie a little to the north and east of the geographical center of the State, in the heart of the corn belt and near the northeast limits of the coal fields. The gentle hill of the town site–uncommon in the central prairie–is a portion of the Bloomington Moraine, the long ridge of drift left by the Wisconsin glacier.

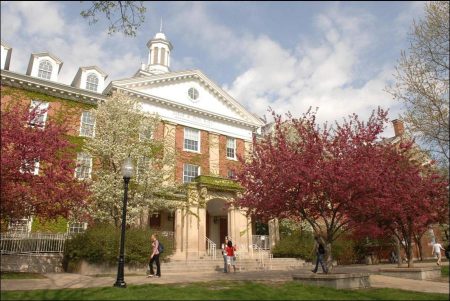

Well wooded, with the courthouse crowning its top, it affords pleasant contrast to the flat geometry of towns that have clustered around the railroads on the unrelieved prairie. Normal, an independent municipality with its own waterworks, fire department, and police force, scorns the appellation of “suburb” and maintains its individuality, centered on Illinois State University.

Leisurely paced, in keeping with its rôle as a university town, Bloomington serves as a trading center for a wide and fertile farm area, and gives little evidence of its industrial underpinning, although its products range from candy bars to heating equipment, from stoves and air-conditioning plants to grain elevators. Its residential area is in a large part gracefully Victorian, but the business section was largely rebuilt after the fire of 1900, when elaborate cornices, decorated façades, and machined gee-gaws were replaced by a soberer functionalism.

In the earliest years of the nineteenth century the large grove at this point, focus of several Indian trails, was known to a few stray trappers and traders. Legend has it that a small party of these rovers of the forests cached a keg of liquor here and inadvertently played absent host to a hilarious party of Indians. It is known, at least, that the site was called Keg Grove when the first permanent settlers came in 1822. The name was shortly changed, because of the profusion of flowers, to Blooming Grove, which prompted a citizen years later to express due gratitude. “Suppose Keg Grove had become transformed into Keg Town,” he said. “How do you suppose Joe Fifer could have ever been elected governor of this State? Or how could Adlai Stevenson, of Keg Town, have been chosen Vice-President of the United States?”

Blooming Grove’s early settlers were largely of British stock, and they brought a desire for the appurtenances of stability. Their community’s name altered decently, they established a school of a sort, and a church with its own pastor, all within two years.

Although Bloomington traces its growth from Blooming Grove, it is not strictly a natural outgrowth of that village. In 1830 James Allin, subsequently ranked first among the city fathers, entered a quarter section of land on the north side of Blooming Grove. Formerly a commissioner of Fayette County, Allin undoubtedly had foreknowledge of the impending subdivision of that county; in December of the same year the legislature at Vandalia created the county of McLean. The following year the county commissioners accepted Allin’s offer of land for the court house, and the town of Bloomington was laid out, adjoining Blooming Grove.

Of all the factors that gave rise to Illinois towns the possession of the county courthouse was far and away the most dependable. Bloomington grew slowly, in a complacent security, until the 1850’s, when three events in quick succession forecast Bloomington’s destiny as a little “big town” rather than as a sleepy and static county seat.

In 1853 Illinois Wesleyan University was organized; the following year the rails of both the Illinois Central and the Chicago and Mississippi Railroads were extended through the town. The latter, now the Alton line, subsequently established its repair shops here, still the industrial mainstay of the city. Then, in 1857, residents remarked their “incredible good fortune” at the awarding of the Illinois State Normal University to North Bloomington, which shortly changed its name to Normal.

In the late 1800’s Bloomington spread its name abroad with Wakefield’s Almanac, published by a patent-medicine king whose specifics stood in rows of vari-colored bottles on the shelf above the wash basin in every kitchen in the Middle West. The publication reached readers of four languages, and made Bloomington the first word to pop into the mind when malaria or chilblains threatened.

Bloomington had its finger in many a State political pie. The State Republican party was organized here in 1856, at the Anti-Nebraska convention that heard Lincoln “Lost Speech.” Speaking extempore, he declared that those who deny freedom to others could not hope to retain it for themselves, that the abolitionists would never withdraw from the Union, that secession by the South would be met by forceful preservation of the Union by the North. The speech made Lincoln a power in the new party, a key-noter of the cause whose popularity swept him inevitably onward to the Presidency. Aligned with Lincoln from the first was the Bloomington Pantagraph, which has been published continuously since 1846.

Bloomington has had rather more than a fair representation of distinguished citizens. Two of her sons, John M. Hamilton and Joseph Fifer, were governors of the State; the portly judge David Davis was one of Lincoln’s most potent political allies; and Adlai Stevenson became Vice President of the United States under Cleveland. The late Margaret Illington, actress, compounded her stage name of syllables in the names of her native State and city, a city that has long had an inexplicable talent for nurturing artists of the world of amusement.

Visits: 109