Arkansas is bounded on the north by Missouri; on the east it is separated from Mississippi and Tennessee by the Mississippi River; to the south is Louisiana; and stretching away to the west are the plains of Oklahoma and Texas. In size it stands twentysixth among the States, with an area of 53,335 square miles; of these, 810 are water.

From the point where the Mississippi first touches Arkansas, lowlands sweep in a constantly widening arc until they run all the way across the State to Oklahoma and Texas. To the northwest rise the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains, reaching an altitude of nearly 3,000 feet. With adjacent elevations that spill over into neighboring States, the Arkansas uplands (classified as the Interior Highland Province) constitute the only mountains between the Appalachians and the Rockies. The line between the lowland and hill sections is remarkably distinct, particularly at the eastern edge of the Ozarks, where the lift from plain to upland is forecast by only a few mound-shaped sentinel hills.

The level eastern and southern parts of the State comprise the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and the West Gulf Coastal Plain. The Alluvial Plain reaches from the river to the edge of the mountains near Little Rock, then narrows southward. The tablelike surface is broken only by a long, narrow strip of hills called Crowley’s Ridge, which runs from the Missouri Line some 150 miles to Helena. Varying in width from half a mile to 12 miles and reaching an altitude of 550 feet near its northern extremity, the Ridge is a notable landmark, its yellow wind-deposited loess topsoil contrasting with the black alluvial earth of the Delta through which it strikes.

Travelers coming from the Mississippi Delta to the West Gulf Coastal Plain notice not so much the slight rise in elevation as a considerable change in the country’s appearance. Near the river vast tracts of the rich land have been cleared and are cultivated in cotton plantations. The clay and sandstone soils farther west, however, are heavily forested, and the occasional farms are of the small, self-sufficient type. The West Gulf Coastal Plain is the great timber belt of Arkansas.

The hill section of the State, like the lowland, is divided into two areas of nearly equal size. To the north are the Ozark plateaus, and to the south is the Ouachita province; between them flows the Arkansas River, through a wide valley which is included in the Ouachita subdivision.

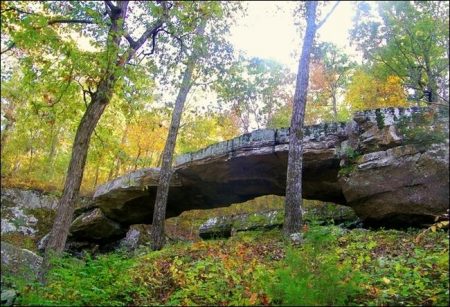

The Ozarks rise from the eastern lowlands in a succession of rolling, tree-covered hills that gradually gain altitude as they continue west and south. The lower portion is known as the Salem and the higher as the Springfield Plateau, but the casual observer will see no particular difference in them. In the extreme northwestern corner of Arkansas the Springfield Plateau is fairly level except where it is cut by deep valleys; here is some of the State’s best land for general farming. On the south the plateaus give way to the Boston Mountains, most rugged of the Ozarks.

By a paradox of topographical classification the Arkansas Valley contains the highest and most impressive peaks of the State. South of the Arkansas Valley are the Ouachita Mountains proper, which are subdivided into the Fourche Mountains, the Novaculite Uplift (so called because it is ringed by ridges of this rock, used for whetstones), and the Athens Piedmont Plateau, which dwindles gradually into the West Gulf Coastal Plain.

Near Oklahoma, the Ouachitas attain considerable height, and a peak of Rich Mountain just across the border tops even Magazine. Pineclad, jumbled, and even less inhabited than the Ozarks, the Ouachitas run from Little Rock’s back door across the western half of the State, and (especially in the Novaculite Uplift) contain a number of rare and valuable minerals.

Visits: 91