Wartime New York City, was, however, to be a far more carefree place than London or Paris, as commentators from areas closer to the war effort neglected no opportunity to show. To be sure, there was for a time a dim-out, ordered not so much through fear of bombs as because the glow of the city’s lights silhouetted shipping for enemy U-boats lurking out at sea. In this halfway measure, the streets were still lighted, a British visitor of 1942 reported; but the “glaring advertisements” which formerly kept Broadway “in perpetual light” were now extinguished, and “all windows above the 10th floor… screened.”

New Yorkers gained some sense of participation in the struggle as air-raid precautions, inaugurated six months before Pearl Harbor, were “practiced and more or less perfected,” sirens were tested, and wardens and plane spotters began to stand watch on tall buildings and rural hilltops. Women took over tasks formerly performed by men–driving cabs, operating elevators, and serving as telegraph messengers–when Selective Service pulled nearly 900,000 New Yorkers into uniform.

The rationing of food and gasoline prompted the most obvious sacrifices, at least for those to whom the black market was not available. But for New Yorkers without close friends or relatives overseas, the sight of servicemen on leave and of the cargo vessels and tankers, “lined up on the Hudson and East River, with their camouflage and artillery, awaiting the formation of convoys,” constituted the closest contact with the shooting war.

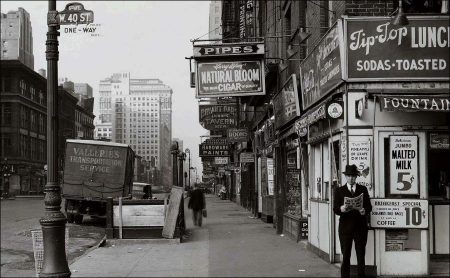

To the casual observer, New York seemed hardly touched by the conflict. The British novelist James L. Hodson saw no sign of a dimout in the winter and spring of 1943-1944; and the naivete of the airraid instructions he found in his hotel bedroom showed him “how far” New York really was “from the war.” At Christmas time the city was gay with holiday decorations.

Cocktail parties preceded dinners boasting menus “astounding to British eyes.” The season was described as “the craziest Christmas for spending” ever known. “There is no war here,” Carlos Romulo contended, in amazement, when he reached New York shortly after the fall of the Philippines. He was horrified at what appeared to be the “holiday air of the people,” rushing madly about–in a “Coney-Island” dim-out–“spending fabulous sums as if they were in the midst of a carnival.”

Only after he had observed the city more closely did the Philippine statesman realize that New York, too, was fighting the war-giving blood, buying bonds, and, above all, moving men and goods in a degree that contributed significantly to victory. The city’s surface frivolity, he ultimately concluded, was in part, at least, a reflection of the way that New York showed its fighting spirit. It was a consequence, too, as other commentators were aware, of the very nature of New York’s most important wartime contribution–the production and movement of goods essential to the war effort.

As production expanded and shipping throve, wages increased, and New Yorkers had more to spend than ever before. At the same time, fewer necessities were available for purchase as a result of wartime restrictions. Hence an unprecedented portion of the worker’s income was at hand for spending at theatres, movie houses, race tracks, restaurants, and bars. It was this, in the opinion of Pierre de Lanux, which caused the erroneous impression that “what was happening overseas had no repercussion on life in the United States” and gave service personnel returning from combat the generally unjustified feeling that New Yorkers were blind to the realities of the conflict.

De Lanux is the authority, too, for New York’s reaction to the victory when it came in 1945. Despite the scarcity of paper, ticker tape rained on Broadway following news of the German armistice in May; and with the defeat of Japan, in August, the sobering implications of Hiroshima did not prevent New Yorkers from staging a real celebration. “From the dignified flag-bedecked residences, uptown, to the gaudily decorated tenements of the East Side and ‘Little Italy,’ the national colors floated amid clouds of confetti, cheering cries, the honking of horns, and the wail of sirens,” the French chronicler reported.

The churches were filled in the morning; then a general rejoicing took possession of the entire city, which reached a climax by evening. At Times Square, the crowds were so dense that the police had difficulty intervening when soldiers and sailors, sharing their joy with the civilians, “embraced and mussed up some of them” in the bargain. “Statisticians will never say exactly how much alcoholic beverage passed from production to consumption that night,” de Lanux asserted, “but the figure would certainly be expressed in tons rather than liters.”

Like the commentators of earlier days, those of the thirties and forties recognized the role of the port in the city’s economy, especially in connection with the nation’s colossal war operation; but increasingly their attention turned to the magnitude of the city’s industrial output, as well. Referring to New York of the mid-forties as “the greatest manufacturing town on earth,” John Gunther pointed out, in his Inside U. S. A., that Manhattan alone employed “more wage earners than Detroit and Cleveland put together,” Brooklyn more than Boston and Baltimore, and Queens more than Washington and Pittsburgh, combined. More persons were engaged in New York’s garment trades than made automobiles in Detroit or steel in Pittsburgh, according to a similar comment in the New York Times.

Visits: 277